Trig identities are notoriously difficult to memorize: here’s how to learn them without losing your mind.

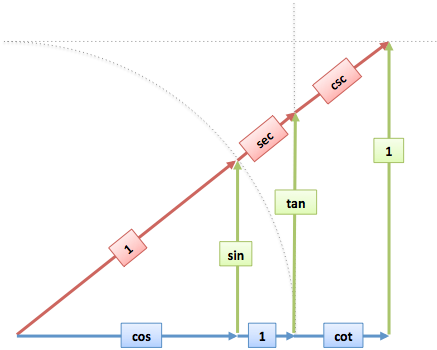

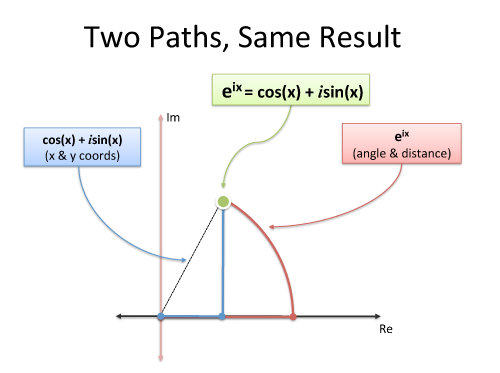

Starting from the Pythagorean Theorem and similar triangles, we can find connections between sin, cos, tan and friends (read the article on trig).

Can we go deeper? Maybe we can connect sine with itself (sin-ception). In math terms, we’re looking for formulas like this (full cheatsheet):

![]()

![]()

Instead of memorizing these bad mamma jammas, let’s learn to draw the formulas. Euler’s Formula makes it easy.

Connections In Algebra

In algebra, we study relationships like this:

![]()

Working out 172 directly is cumbersome. But we can simplify it to:

![]()

In the computer era, sure, we can just crunch 172 directly. The important aspect is realizing that (a + b)2 can be broken into simpler ingredients: a2, b2, a, b. This is useful in factoring, simplifying equations, and so on.

Connections In Trig

Let’s turn trig into plain English. What does this mean?

![]()

Remembering that sine is “height (as a percentage of max)”, this equation asks: If we add two angles, what is their total height?

A quick guess might be to combine the individual heights:

![]()

It looks clean, but isn’t quite right. If we keep adding up angles, their height increases until the max (100%), then starts decreasing.

The relationship between angle and height can’t be simple addition.

Now here’s the weird thing: I can draw what the new height should be (It’s right there!), but I can’t turn my drawing into an equation.

Or can I?

Drawing With Euler’s Formula

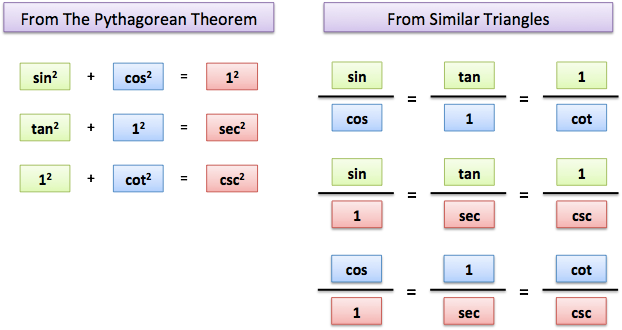

Euler’s Formula lets us create a circular path using complex numbers:

Crucially, multiplying complex numbers performs a rotation. Aha! We can use Euler’s Formula to draw the rotation we need:

- Start with 1.0, which is at 0 degrees.

- Multiply by eia, which rotates by a.

- Multiply by eib, which rotates by b.

- Final position = 1.0 · eia · eib = ei(a+b), or 1.0 at the angle (a+b)

The complex exponential ei(a+b) is pretty gnarly. Just like breaking apart 172, let’s multiply out the pieces:

![\displaystyle{ = [\cos(a) + i\sin(a)] \cdot [\cos(b) + i\sin(b)]} \displaystyle{ = [\cos(a) + i\sin(a)] \cdot [\cos(b) + i\sin(b)]}](/wp-content/plugins/wp-latexrender/pictures/b8348a05f6bde590fbc0c377eef16961.png)

![\displaystyle{ = [\cos(a)\cos(b) - \sin(a)\sin(b)] + i[\sin(a)\cos(b) + \sin(b)\cos(a)]} \displaystyle{ = [\cos(a)\cos(b) - \sin(a)\sin(b)] + i[\sin(a)\cos(b) + \sin(b)\cos(a)]}](/wp-content/plugins/wp-latexrender/pictures/d6ff14e07472f3125dbf219ddefc1ff4.png)

![\displaystyle{ = [\text{combined width}] + i[\text{combined height}]} \displaystyle{ = [\text{combined width}] + i[\text{combined height}]}](/wp-content/plugins/wp-latexrender/pictures/cbc82c042414857413c2508ccea16b70.png)

Now we’re talking! This version easily separates the horizontal position (real component) and vertical position (imaginary component):

- Combined height: sin(a + b) = sin(a)cos(b) + sin(b)cos(a)

- Combined width: cos(a + b) = cos(a)cos(b) – sin(a)sin(b)

Boom: two annoying-to-remember trig identities in a single computation. Not a bad deal.

Understanding The Equation

Now that we’ve found the equation, let’s grok its meaning. When we add the heights, here’s what’s happening:

- The full height of the blue triangle (sin(a)) can’t be used, since the red triangle doesn’t extend as far. (Why? When we add angle b, we’re moving at a steeper angle with the same hypotenuse. We gained vertical distance and lost horizontal distance.) We’re effectively “sliding back” sin(a), reducing it by a factor of cos(b).

- The full height of the red triangle (sin(b)) can’t be used either, since it’s at an angle. We’re “turning” sin(b), reducing it by a factor of cos(a).

Remember that sine and cosine are percentages. In this case,

![\displaystyle{\sin(a + b) = [\sin(a) \times \text{\% we get for a}] + [\sin(b) \times \text{\% we get for b}]} \displaystyle{\sin(a + b) = [\sin(a) \times \text{\% we get for a}] + [\sin(b) \times \text{\% we get for b}]}](/wp-content/plugins/wp-latexrender/pictures/c3a8f5c897803eaf763b431881625139.png)

or

![\displaystyle{\sin(a + b) = [\sin(a) \times \cos(b)] + [\sin(b) \times \cos(a)]} \displaystyle{\sin(a + b) = [\sin(a) \times \cos(b)] + [\sin(b) \times \cos(a)]}](/wp-content/plugins/wp-latexrender/pictures/171dc2b285c58244a2899f45f94ad6eb.png)

Sure, we would like to get the full height of each triangle. But from the diagram, we see a slides back and b is twisted, so height we actually get is reduced. Think of each cosine as a tax on your height, reducing the amount you take home. (Have a height of .90? That’s nice, Papa Cosine will let you keep 75%. Pay up the rest, sucka!).

Now, what happens for small angles, like sin(.01 + .02)?

We could plug and chug this. But I’m guessing the result is about:

![]()

Why? My mental diagram for small angles is this:

There’s no perceptible difference between the ideal heights (sin(a) and sin(b)) and the “taxed” versions (sin(a)cos(b) and sin(b)cos(a)).

- For tiny angles, sin(a + b) is a vertical line. It barely loses any height due to the parts sliding or twisting.

- For small angles, cosine (the percent we keep), is close to 100%. We’re keeping the vast, vast majority of the height we have.

- sin(x) sim x is a common approximation for small angles (often used in Calculus). Essentially, it says sin(x) is a line for a brief time period. For small angles, sin(a + b) sim sin(a) + sin(b) sim a + b.

For cosine, we have a similar diagram:

- This time, the conversion factor matches up (cosine with cosine, sine with sine).

- The full width of the first triangle (cos(a)) gets scaled down to match the width of the second.

- The sine term is negative since it pushes us backwards, reducing our height. We can use similar triangles to extract out this piece.

I’m not typically thinking about the parts in the diagram, though it’s nice to see how they work a few times. If you just need the trig identity, crank through it algebraically with Euler’s Formula.

Why do we care about trig identities?

Good question. A few reasons:

1. Because you have to (the worst reason). Many trig classes have you memorize these identities so you can be quizzed later (argh). You don’t need to memorize them, you can work out the formula in about a minute. Save your precious brain space for something else.

2. We can now “factor” trig functions into simper parts. We can now separate sine into smaller parts, which is useful in Calculus.

For example, to find the derivative of sine, we need:

and we let dx go to zero. This is tricky to work on directly, but using the sin(a + b) formula we have

As dx goes to zero, cos(dx) = 1 (zero angle is full width), so we have:

![]()

And as dx goes to zero, sin(dx) and dx become equal:

Plugging this in, we get cos(a) as the derivative of sin(a). Phew! Working with trig functions isn’t always easy, but at least it’s manageable.

3. It’s computationally efficient. If you’re doing a computer graphics, and frequently calculating sine/cosine (for dot products let’s say), trig identities are useful shortcuts. In the past, these identities were used similar to log tables to make hand-done calculations easier.

4. Math is about seeing connections. Because trig functions are derived from circles and exponential functions, they seem to show up everywhere. Sometimes you simplify a scenario by going from trig to exponents, or vice versa.

5. Deepen your knowledge of Euler’s Formula. Master Euler’s formula and you’ve mastered circles. And from there, the world! (Editor’s note: Kalid’s pinky appears to be affixed to his mouth. We’re working on it.)

See, Euler’s formula lets us draw a circle and read off a position. That’s amazing! We can avoid a lot of painful geometry with a few multiplications. If you’re doing any advanced math, letting Leonhard Euler deep into your soul is well worth it. He’s good company.

That’s it for today. Happy math.

Appendix: Resources and Extended Formulas

You can mix & match trig identities to create a bunch of new ones.

Subtraction formula: replace b with -b

![]()

Double-angle formula: replace b with a

![]()

This makes sense: after accounting for the conversion factor, we add the height to itself.

![]()

Half-angle formula: replace and solve

Start with the double-angle formula and solve for sin(a), which is half the angle used in sin(2a). Trig without tears (a great resource and name) has more details:

http://brownmath.com/twt/double.htm

A few other references I found helpful:

- http://www.tc.umn.edu/~nydic001/docs/unpubs/Eulers_Formula_and_Trig_Identities.pdf

- https://www.wyzant.com/resources/lessons/math/trigonometry/eulers-formula-trig-identities

- http://www.ctralie.com/Teaching/Euler/

- http://kunklet.people.cofc.edu/MATH220/euler.pdf

Leave a Reply

16 Comments on "Easy Trig Identities With Euler’s Formula"

Nice article . Thanks.

Well done again, superbly done.

It gives beginners like me to think intutively about derivative of tan function

Tan is not bounded by circle but it behaves like sine it does not return it shoots to infinity.as distance to wall is always same whole benefit of increasing angle recieved by wall height (no discount) the percentage of increase in wall height is solely dependent on height of ladder hypotenuse.

Kindly comment sir, if I am on right track.thank u for such beautiful insight

Hi Aisha, glad you enjoyed it! Yep, tan(x) is similar to sin(x), except it grows without bound (until it crosses 90 degrees). I’d like to do a follow-up on the derivatives of trig functions, but you’re on the right track.

Nice explanation!

Some typos:

We could plug and chug this. But I’m guessing the result is about:

\displaystyle{\sin(.01 + .02) \sim \sin(.03) \sim .03}

instead of

\displaystyle{\sin(.01 + .02) \sim \sin(.03) ~ .03}

The ~ makes just a small space and I think it should be \sim.

Also please search {sin(dx)}, sin(2a), sin(a-b), and sin(a+a). I think these are all “\sin” instead of just “sin”.

Thanks for the great article!

@Hitoshi: Thank you! Just fixed those all up :).

I don’t understand the scaling. For instance, why is Sin(B) scaled by Cos(A) ?

Good question. So, the simple case we might think:

sin(a + b) = sin(a) + sin(b)

That equation, if correct, means we combine the full height of each angle when moving around a circle (for example, a 30 and 20 degree angle have the same height as a 50 degree angle). However, as we move, we are curving, so we don’t really get the full “sin(b)” height. The fraction we actually get [cos(a)] is what we need to scale it down by.

Another way to put it: if we added heights directly, that means adding angles [sin(1), sin(2), sin(3)] would just keep increasing our height. But our height on a circle tops out at 90 degrees, and 91 degrees is actually less tall. Without the cos(a) factor, we can’t reduce our height to account for this.

I see. But, why is the scaling factor Cos(A) & not anything else ?

This.

I don’t see how cos(b) should be the ratio we want to scale back sin(a) with?

@Marcus

The hypotenuse of the bottom blue triangle is always 1, as we’re in a unit circle.

The length of the bottom side of the red triangle is between 0 and 1, and is equal to cos(b).

So the red triangle will cover a distance on the hypotenuse of the blue triangle, and that distance will equal cos(b). This is also the percentage of the blue hypotenuse that is covered, as the length is constant at 1.

So if cos(b) = 0.5, exactly 50% of the bottom hypotenuse is covered by the top triangle.

If you reduce one side of a triangle, all other sides of said triangle are reduced by the same ratio. If you make the hypotenuse 50% smaller, the height will be 50% smaller as well. So the actual height becomes sin(a) * 0.5. Or sin(a) * cos(b) in the general case.

In essence, the top triangle is supported by a triangle that is exactly the same as the bottom one but scaled down by a factor of cos(b), which reduces the height by a factor of cos(b).

There’s a nice diagram illustrating how sin(b) is scaled by cos(b) here: http://math.stackexchange.com/a/1342.

Looking at the diagram on the left and given that cos(a) = adjacent / hypotenuse (where hypotenuse is sin(b)), rearranging the equation gives:

adjacent = cos(a) * hypotenuse = cos(a) * sin(b)

Typo in the above comment, it’s “illustrating how sin(b) is scaled by cos(a)”.

nice math thanks alot , would you help me to prove that ” if ABC is a triangle with AB = AC then 2sinB.cosC = sin A ” using complex numbers >

It was great to stumble upon this post. Thanks for the sharing, I also found a useful service for forms filling. If you ever need to fill out a form, here is

http://goo.gl/VYWJdZa really useful tool. Very easy to navigate and use.You saved my life, thanks!