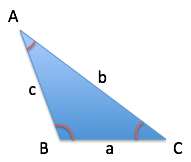

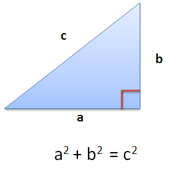

The Law of Cosines is presented as a geometric result that relates the parts of a triangle:

![]()

While true, there’s a deeper principle at work.

The Law of Interactions: The whole is based on the parts and the interaction between them.

The wording “Law of Cosines” gets you thinking about the mechanics of the formula, not what it means. Part of my learning strategy is rewording ideas into ones that make sense.

The Law of Cosines, after cranking through geometric steps we’re prone to forget, looks like $c^2 = a^2 + b^2 – 2ab\cos(C)$.

This is suspiciously like the expansion that if $c = (a + b)$, then $c^2 = a^2 + b^2 + 2ab$

The difference is that $2ab$ has an extra factor, $\cos(C)$, which measures the “actual overlap percentage” ($2ab$ assumes we fully overlap, i.e. where $\cos(C) = 1$).

So, the Law of Cosines is really a generalization of how $c^2 = (a + b)^2$ expands when components aren’t fully lined up. We’re treating geometric lines as terms in an algebraic expansion.

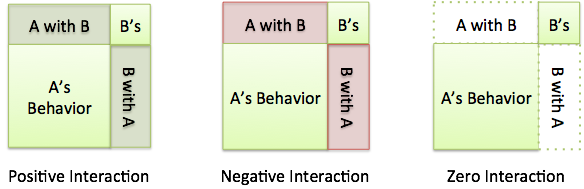

Analogy: The Assistant Chef

Imagine a restaurant with a single chef, Alice. She’s overworked, so Bob is hired as her assistant (sous chef).

Based on Alice’s current performance, and Bob’s performance in his interview, what happens when they work together?

Surely the new result must be their combined effort:

![]()

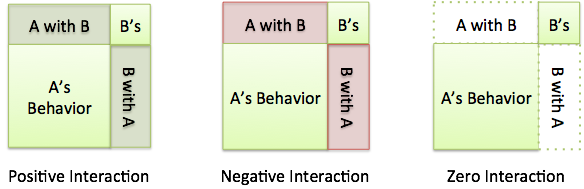

Hah! Office workers everywhere are rolling their eyes. You can’t just assume people contribute identically when they’re put together: there are interactions to account for.

Beyond their individual contributions, the two might slow each other down (Where’d you put the whisk again?), or find ways to work together (I’m peeling carrots anyway, use some of mine.).

In a system with several parts, start with the individual contributions and then ask if their interaction will:

- Help each other

- Hurt each other

- Ignore each other

The original idea that “Total = Alice + Bob” is more generally expressed as:

![]()

Exploring The Scenario

We need to separate the list of participants (Alice, Bob) from the result of their interaction.

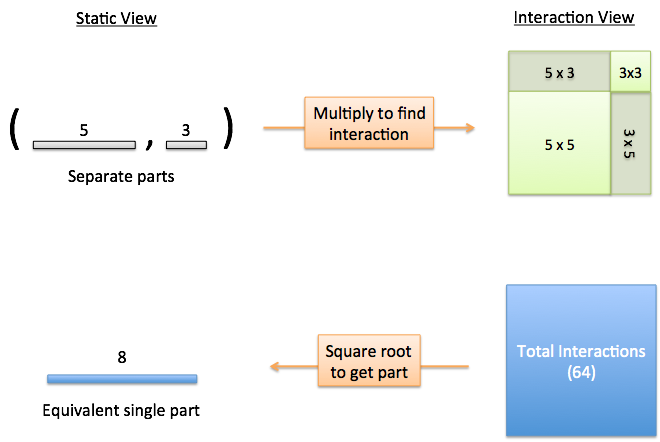

Take the numbers 5 and 3. We can write them like so:

- Parts = (5, 3)

and we’re pretty sure they combine to make 8. But is there another way to get that conclusion?

Yes: we multiply. Beyond repeated counting, multiplication shows what happens when the parts of a system interact:

![]()

We’ve gone from “parts view”, $(5, 3)$, to “interaction view”, $(5 + 3)^2$. The result of interaction mode says the system would result in 64 if it did interact with itself.

One caveat: when going to interaction view, we wrote down $(5 + 3)(5 + 3)$, but we can’t simplify $(5 + 3) = 8$ on the outset. We’re using addition for bookkeeping until multiplication can combine the parts.

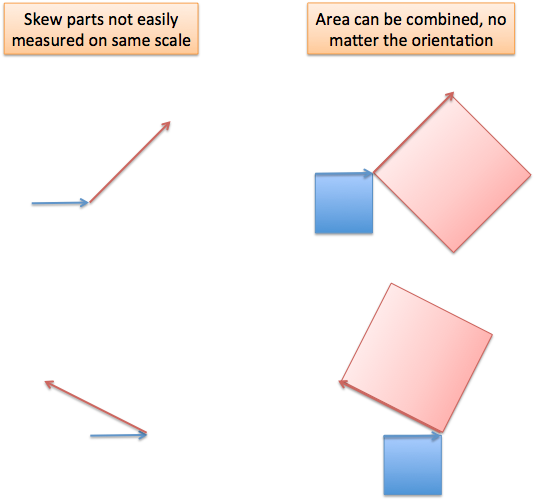

Oh, another caveat: why can we just add the interactions, but not the parts? Great question. The individual parts might be pointing in different dimensions, and don’t line up nicely on the same scale. The interacting parts turn into area, which can be combined to the same result no matter the orientation.

(I’ll investigate this concept more in a follow-up. It’s a neat idea that area is a generic, easily combinable quantity but individual paths are not.)

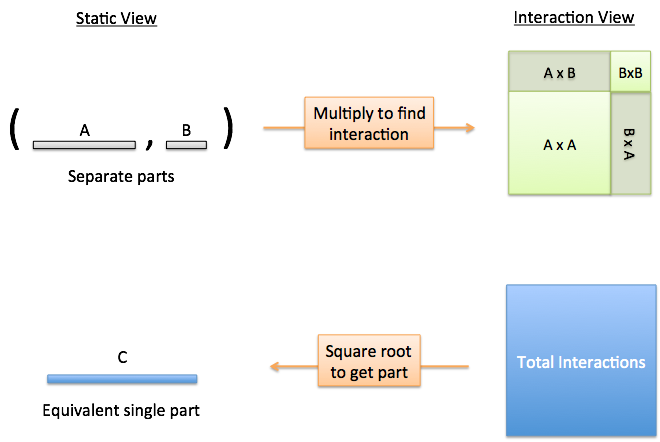

Generalizing the Principle

Simple setups like (5, 3) are easy to think through, like eyeballing $2x + 3 = 7$ and guessing $x = 2$. But a more complex scenario like $x^2 + 3x = 15$ requires a systematic approach.

The Law of Cosines is a systematic approach to working through the parts:

- List the parts

- Get every interaction as area

- Add to find the total contribution

- Convert into the equivalent “single part”

The last step is often implied. Once we’ve merged the jumble of interactions, we want the single part that could represent the entire system. Is there a single person (Charlie) whose efforts are identical to that of Alice and Bob working together?

The Law of Cosines gives us a way to find Charlie.

What’s the Deal with Cosine?

When two parts interact, they can help, hurt, or ignore each other:

- Perfect alignment means they help 100% (5 and 3)

- Perfect mis-alignment means they hurt 100% (5 and -3)

- Partial alignment or mis-alignment means they help or hurt by a percentage

- No alignment means they ignore each other

How do we measure alignment? With cosine.

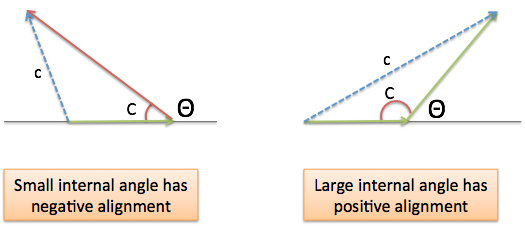

Using our trig analogy, cosine is the percentage an angle moves along the ground.

A 0-degree angle follows the ground perfectly (100%), and moving vertically doesn’t follow it at all (0%). Other angles are a fraction in-between.

If the parts in our system can be written as paths, and we know the angle between them is theta ($\theta$), then we can measure the overlap with cosine. One path acts as the ground, and the other is the path we’re following:

![]()

![]()

When paths are perfectly aligned, their full strength is used ($ab$ and $ba$). The interaction factor $\cos(\theta)$ modifies that strength to show much they actually work together.

So, our jumble of interactions becomes:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Phew! And that’s the Law of Cosines: collect every interaction, account for the alignment, and simplify it to a single part. (The formula is usually written without the square root, but usually you want $c$, not $c^2$.)

Now, why is the Law of Cosines often written with a negative sign? Well, the assumption is that in a typical triangle, a small internal angle $C$ means the sides are negatively aligned, while theta ($\theta$) is an external look at their alignment:

Similarly, a large internal angle means the sides are positively aligned, and will help each other. Typically, a small angle means you’re moving in the same direction, but this internal/external difference means we reverse the sign.

Personally, I don’t memorize whether there’s a positive or negative sign: I think about whether the parts will help or hurt each other in the scenario, and make the interaction positive or negative. Don’t be a slave to the formula.

Quick Practice Problem

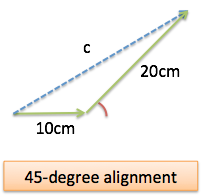

Let’s say my triangle has side $a = 10$ and side $b = 20$. What is side $c$ when the angle between $a$ and $b$ is:

45 degrees in alignment

Here, we need the Law of Cosines. $a$ and $b$ are pointing partially in the same direction. We switch to interaction mode to get to a common, combinable unit (area):

- $a^2 = 100$

- $b^2 = 400$

- $2ab = 2 \cdot 10 \cdot 20 = 400$, but we need to adjust by the interaction factor. That is $\cos(45) = .707$, so the real interaction factor is $400 \cdot .707 = 282.8$

The overall interactions are:

![]()

and the equivalent single side (c) is:

![]()

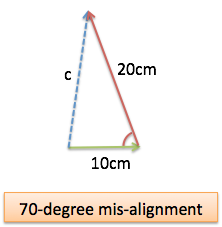

70 degrees in mis-alignment

Again, we need the Law of Cosines. We can see that the angles fight each other, so the interaction will be negative:

![]()

![]()

Our intuition says this arrangement should be smaller than the previous one (since the sides aren’t working together), and it is.

Full alignment or mis-alignment

When our “triangle” has an angle of 0 degrees (or 180), all the parts are lying flat. Here, the parts are in the same dimension, and can be treated as regular numbers:

- Fully aligned: 10 + 20 = 30

- Fully mis-aligned: 10 – 20 = -10 (pointing in direction of B).

The Law of Cosines still works, of course:

- Full alignment: $a^2 + b^2 + 2ab\cos(\theta) = 100 + 400 + 400\cos(0) = 900$ and $c = \sqrt{900} = 30$

- Full mis-alignment: $a^2 + b^2 – 2ab\cos(\theta) = 100 + 400 + 400\cos(180) = 100$ which means $c = \sqrt{100} = 10$ (pointing backwards).

Again, we shouldn’t robotically follow the formula: have a rough idea what the result should be, and think through the calculations. (“The overall interaction is this, so the individual side would that…”).

Thinking of interactions is one interpretation: next time, we’ll see it as the Law of Projections.

Happy math.

Appendix: Pythagorean Theorem

The Law of Cosines resembles the Pythagorean Theorem, no?

Now you might suspect why. The Pythagorean Theorem is the special case of zero interaction, which happens when the sides are at right angles. After all, 90 degree angle is vertical, and has 0% overlap with the ground.

The Law of Cosines becomes:

![]()

![]()

If we know the parts won’t interact, we can ignore interaction effects. However, the self-interactions are still there and must be combined: $a^2$ and $b^2$ are fine, but the crossover terms $ab$ and $ba$ disappear.

Here’s another version of the Pythagorean Theorem. We can’t combine $a$ and $b$ directly, so combine their interactions and reduce them to a single part:

![]()

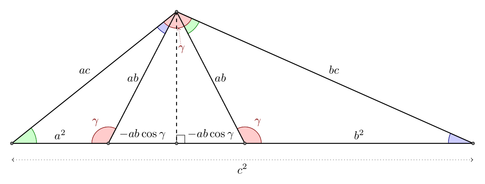

Appendix: The Geometric Proof

You might be hankering for a geometric proof. Here’s one from quora, based on a paper by Knuth:

The insight is that we take our original $a-b-c$ triangle and scale it by $a$ (giving the $a^2-ab-ac$ triangle) and $b$ (giving the $ab-b^2-bc$ triangle). These two triangles build a larger, similar triangle $ac-bc-c^2$, and with some trig, the bottom portion can be shown to equal $a^2 + b^2 – 2ab\cos(\theta)$.

While interesting, I don’t like these types of proofs up front. The Law of Cosines is about interactions, not re-arranging triangles. Does this explanation get you thinking about what cosine represents? About when it should be positive, negative, or zero?

Appendix: Another Way to Remember

Imagine sides A and B are pointing in the same direction along the horizontal number line. This means $c = a + b$ and the Law of Cosines reduces to:

![]()

So, for a 180-degree interior angle, we get a regular algebraic statement. This helps me remember, on the fly, when to add vs. subtract. We add $2ab\cos(\theta)$ when the interior angle is large.

ADEPT Summary

| Concept | Law of Cosines |

|---|---|

| Analogy | Imagine an assistant chef whose interactions may (or may not) be helpful. |

| Diagram |  |

| Example | Suppose $a = 10$ and $b = 20$ in a triangle. If they are aligned 45-degrees, their interaction is $a^2 + b^2 + 2ab\cos(45) = 782.8$ and the remaining side is $\sqrt{782.8} = 27.97$ units long. |

| Plain-English | The Law of Interactions: The whole is based on the parts and the interaction between them. |

| Technical | Triangle with internal angle C: $c^2 = a^2 + b^2 – 2ab\cos(C) $ General interaction: $c^2 = a^2 + b^2 + 2ab\cos(\theta) $ |