Interest rates are confusing, despite their ubiquity. This post takes an in-depth look at why interest rates behave as they do.

Understanding these concepts will help understand finance (mortgages & savings rates), along with the omnipresent e and natural logarithm. Here’s our cheatsheet:

| Term | Formula | Description & Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Simple | Fixed, non-growing return (bond coupons) | |

| Compound (Annual) |

Changes each year (stock market, inflation) | |

| Compound (n times per year) |

Changes each month/week/day (savings account) | |

| Continuous Growth | Changes each instant (radioactive decay, temperature) | |

| APR | Annual Percentage Rate (compounding not included) | |

| APY | Annual Percentage Yield (all compounding effects included) | |

- P = principal, your initial investment (i.e., \$1,000)

- r = interest rate (i.e., 5% per year)

- n = number of time periods (i.e., 3 years)

And a quick calculator to convert APR to APY:

Why the fuss?

Interest rates are complex. Like Roman numerals and hieroglyphics, our first system “worked” but wasn’t quite ideal.

In the beginning, you might have had 100 gold coins and were paid 12% per year (percent = per cent = per hundred — those Roman numerals still show up!). It’s simple enough: we get 12 coins a year. But is it really 12?

If we break it down, it seems we earn 1 gold a month: 6 for January-June, and 6 for July-December. But wait a minute — after our June payout we’d have 106 gold in July, and yet earn only 6 during the rest of the year? Are you saying 100 and 106 earn the same amount in 6 months? By that logic, do 100 and 200 earn the same amount, too? Uh oh.

This issue didn’t seem to bother the ancient Egyptians, but did raise questions in the 1600s and led to Bernoulli’s discovery of e (sorry math fans, e wasn’t discovered via some hunch that a strange limit would have useful properties). There’s much to say about this riddle — just keep this in mind as we dissect interest rates:

- Interest rates and terminology were invented before the idea of compounding. Heck, loans were around in 1500 BC, before exponents, 0, or even the decimal point! So it’s no wonder our discussions can get confusing.

- Nature doesn’t wait for a human year before changing. Interest earnings are a type of “growth”, but natural phenomena like temperature and radioactive decay change constantly, every second and faster. This is one reason why physics equations model change with “e” and not “$(1+r)^n$”: Nature rudely ignores our calendar when making adjustments.

Learn the Lingo

As a result of these complications, we need a few terms to discuss interest rates:

- APR (annual percentage rate): The rate someone tells you (“12% per year!”). You’ll see this as “r” in the formula.

- APY (annual percentage yield): The rate you actually get after a year, after all compounding is taken into account. You can consider this “total return” in the formula. The APY is greater than or equal to the APR.

APR is what the bank tells you, the APY is what you pay (the price after taxes, shipping and handling, if you get my drift). And of course, banks advertise the rate that looks better.

Getting a credit card or car loan? They’ll show the “low APR” you’re paying, to hide the higher APY. But opening a savings account? Well, of course they’d tout the “high APY” they’re paying to look generous.

The APY (actual yield) is what you care about, and the way to compare competing offers.

Simple Interest

Let’s start on the ground floor: Simple interest pays a fixed amount over time. A few examples:

- Aesop’s fable of the golden goose: every day it laid a single golden egg. It couldn’t lay faster, and the eggs didn’t grow into golden geese of their own.

- Corporate bonds: A bond with a face value of \$1000 and 5% interest rate (coupon) pays you \$50 per year until it expires. You can’t increase the face value, so \$50/year is what you will get from the bond. (In reality, the bond would pay \$25 every 6 months).

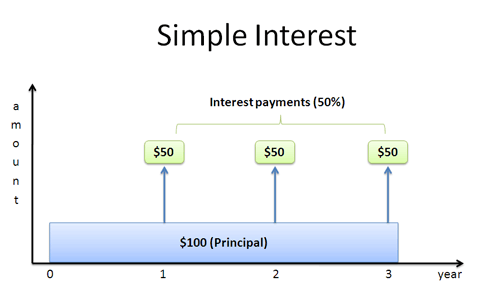

Simple interest is the most basic type of return. Depositing \$100 into an account with 50% simple (annual) interest looks like this:

You start with a principal (aka investment) of \$100 and earn \$50 each year. I imagine the blue principal “shoveling” green money upwards every year.

However, this new, green money is stagnant — it can’t grow! With simple interest, the \$50 just sits there. Only the original \$100 can do “work” to generate money.

Simple interest has a simple formula: Every period you earn P * r (principal * interest rate). After n periods you have earned:

[Unparseable or potentially dangerous latex formula. Error 6 ]

This formula works as long as “r” and “n” refer to the same time period. It could be years, months, or days — though in most cases, we’re considering annual interest. There’s no trickery because there’s no compounding — interest can’t grow.

Simple interest is useful when:

- Your interest earnings create something that cannot grow more. It’s like the golden goose creating eggs, or a corporate bond paying money that cannot be reinvested.

- You want simple, predictable, non-exponential results. Suppose you’re encouraging your kids to save. You could explain that you’ll put aside \$1/month in “fun money” for every \$20 in their piggybank. Most kids would be thrilled and buy comic books each month. If your last name is Greenspan, your kid might ask to reinvest the dividend.

In practice, simple interest is fairly rare because most types of earnings can be reinvested. There really isn’t an APR vs APY distinction, since your earnings can’t change: you always earn the same amount per year.

Really Understanding Growth

Most interest explanations stop there: here’s the formula, now get on your merry way. Not here: let’s see what’s really happening.

First, what does an interest rate mean? I think of it as a type of “speed”:

- 50 mph means you’ll travel 50 miles in the course of an hour

- r = 50% per year means you’ll earn 50% of your principal in the course of a year. If P = \$100, you’ll earn \$50/year (your “speed of money growth”).

But both types of speed have a subtlety: we don’t have to wait the full time period!

Does driving 50 mph mean you must go a full hour? No way! You can drive “only” 30 minutes and go 25 miles (50 mph * .5 hours). You could drive 15 minutes and go 12.5 miles (50 mph * .25 hours). You get the idea.

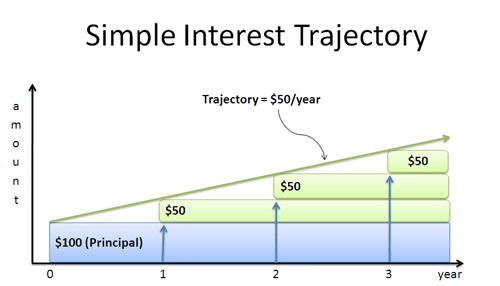

Interest rates are similar. An interest rate gives you a “trajectory” or “pace” to follow. If you have \$100 at a 50% simple interest rate, your pace is \$50/year. But you don’t need to follow that pace for a full year! If you grew for 6 months, you should be entitled to \$25. Take a look at this:

We start with \$100, in blue. Each year that blue contributes \$50 (in green) to our total amount. Of course, with simple interest our earnings are based on our original amount, not the “new total”. Connecting the dots gives us a trendline: we’re following a path of \$50/year. Our payouts look like a staircase because we’re only paid at the end of the year, but the trajectory still works.

Simple interest keeps the same trajectory: we earn “P*r” each year, no matter what (\$50/year in this case). That straight line perfectly predicts where we’ll end up.

The idea of “following a trajectory” may seem strange, but stick with it — it will really help when understanding the nature of e.

One point: the trajectory is “how fast” a bank account is growing at a certain moment. With simple interest, we’re stuck in a car going the same speed: \$50/year, or 50 mph. In other cases, our rate may change, like a skydiver: they start off slow, but each second fall faster and faster. But at any instant, there’s a single speed, a single trajectory.

(The math gurus will call this trajectory a “derivative” or “gradient”. No need to hit a mosquito with the calculus sledgehammer just yet.)

Basic Compound Interest

Simple interest should make you squirm. Why can’t our interest earn money? We should use the bond payouts (\$50/year) to buy more bonds. Heck, we should use the golden eggs to fund research into cloning golden geese!

Compound growth means your interest earns interest. Einstein called it “one of the most powerful forces in nature”, and it’s true. When you have a growing thing, which creates more growing things, which creates more growing things… your return adds up fast.

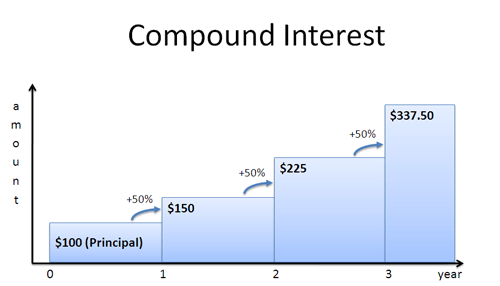

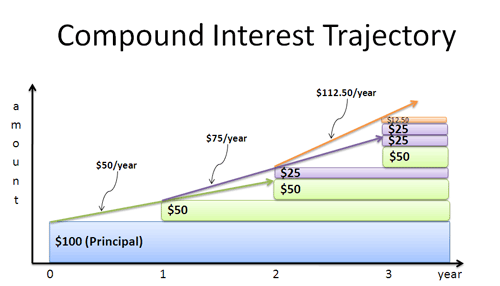

The most basic type is period-over-period return, which usually means “year over year”. Reinvesting our interest annually looks like this:

We earn \$50 from year 0 – 1, just like with simple interest. But in year 1-2, now that our total is \$150, we can earn \$75 this year (50% * 150) giving us \$225. In year 2-3 we have \$225, so we earn 50% of that, or \$112.50.

In general, we have (1 + r) times more “stuff” each year. After n years, this becomes:

![]()

Exponential growth outpaces simple, linear interest, which only had \$250 in year 3 (100 + 3*50). Compound growth is useful when:

- Interest can be reinvested, which is the case for most savings accounts.

- You want to predict a future value based on a growth trend. Most trends, like inflation, GDP growth, etc. are assumed to be “compoundable”. Yearly GDP growth of 3% over 10 years is really $(1.03)^10 = 1.344$, or a 34.4% increase over that decade.

Interest as a Factory

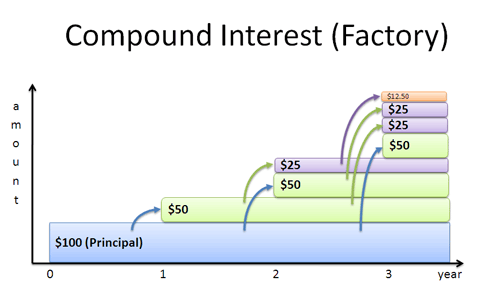

The typical interpretation sees money as a “blob” that grows over time. This view works, but sometimes I like to see interest earnings as a “factory” that generates more money:

Here’s what’s happening:

- Year 0: We start with \$100.

- Year 1: Our \$100 creates a \$50 “bond”.

- Year 2: The \$100 generates another \$50 bond. The \$50 generates a \$25 bond. The total is 50 + 25 = 75, which matches up.

- Year 3: Things get a bit crazy. The \$100 creates a third \$50 bond. The two existing \$50 bonds make \$25 each. And the \$25 makes a 12.50.

- Years 4 to infinity: Left as an exercise for the reader. (Don’t you love that textbook cop out?)

This is an interesting viewpoint. The \$100 just mindlessly cranks out \$50 “factories”, which start earning money independently (notice the 3 blue arrows from the blue principal to the green \$50s). These \$50 factories create \$25 factories, and so on.

The pattern seems complex, but it’s simpler in a way as well. The \$100 has no idea what those zany \$50s are up to: as far as the \$100 knows, we’re only making \$50/year.

So why’s this viewpoint useful?

- You can separate the impact of the parent (\$100) from the children. For example, at Year 3 we have \$337.50 total. The parent has earned \$150 (“3 * 50% * \$100 = \$150”, using the simple interest formula!). This means the various “children” have contributed \$337.50 – \$150 – \$100 = \$87.50, or about 1/3 the total value.

- Breaking earnings into components helps understand e. Knowing more about e is a good thing because it shows up everywhere.

And besides, seeing old ideas in a new light is always fun. For one of us, at least.

Understanding the Trajectory

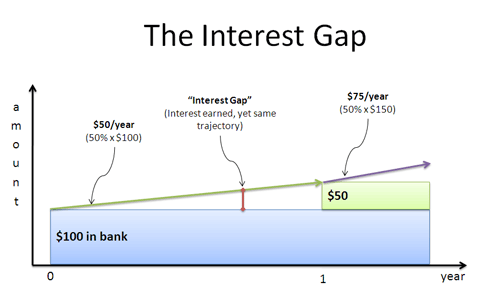

Oh, we’re not done yet. One more insight — take a look at our trajectory:

With simple interest, we kept the same pace forever (\$50/year — pretty boring). With annually compounded interest, we get a new trajectory each year.

We deposit our money, go to sleep, and wake up at the end of the year:

- Year 1: “Hey, waittaminute. I’ve got \$150 bucks! I should be making \$75/year, not \$50!”. You yell at your banker, crank up the dial to \$75/year, and go to sleep again.

- Year 2: “Hey! I’ve got \$225, and should be making \$112.50 per year!”. You scream at your bank and get the rate adjusted.

This process repeats forever — we seem to never learn.

Compound Interest Revisited

Why are we waiting so long? Sure, waiting a year at a time is better than waiting “forever” (like simple interest), but I think we can do better. Let’s zoom in on a year:

Look at what’s happening. The green line represents our starting pace (\$50/year), and the solid area shows the cash in our account. After 6 months, we’ve earned \$25 but don’t see a dime! More importantly, after 6 months we have the same trajectory as when we started. The interest gap shows where we’ve earned interest, but stay on our original trajectory (based on the original principal). We’re losing out on what we should be making.

Imagine I took your money and returned it after 6 months. “Well, ya see, I didn’t use it for a full year, so I don’t really owe you any interest. After all, interest is measured per year. Per yeeeeeaaaaar. Not per 6 months.” You’d smile and send Bubba to break my legs.

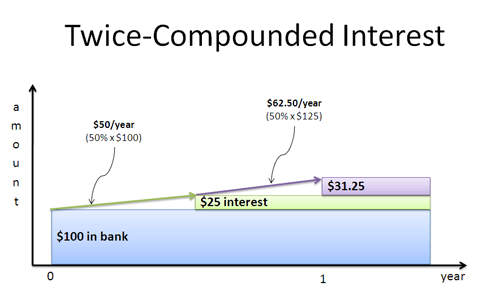

Annual payouts are man-made artifacts, used to keep things simple. But in reality, money should be earned all the time. We can pay interest after 6 months to reduce the gap:

Here’s what happened:

- We start with \$100 and a trajectory of \$50/year, like normal

- After 6 months we get \$25, giving us \$125

- We head out using the new trajectory: 50% * \$125 = \$62.5/year

- After 6 months we collect 62.5/year times .5 year = 31.25. We have 125 + 31.25 = 156.25.

The key point is that our trajectory improved halfway through, and we earned 156.25, instead of the “expected” 150. Also, early payout gave us a smaller gap area (in white), since our \$25 of interest was doing work for the second half (it contributed the extra 6.25, or \$25 * 50% * .5 years).

For 1 year, the impact of rate r compounded n times is:

![]()

In our case, we had $(1 + 50\%/2)^2$. Repeating this for t years (multiplying t times) gives:

![]()

Compound interest reduces the “dead space” where our interest isn’t earning interest. The more frequently we compound, the smaller the gap between earning interest and updating the trajectory.

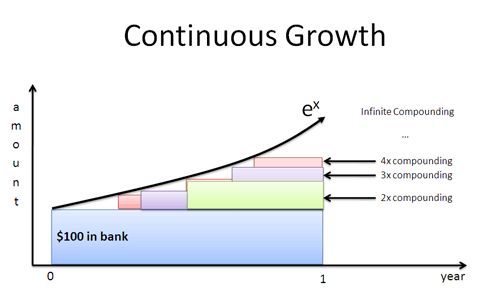

Continuous Growth

Clearly we want money to “come online” as fast as possible. Continuous growth is compound interest on steroids: you shrink the gap into oblivion, by dividing the year into more and more time periods:

The net effect is to make use of interest as soon as it’s created. We wait a millisecond, find our new sum, and go off in the new trajectory. Except it’s not every millisecond: it’s every nanosecond, picosecond, femtosecond, and intervals I don’t know the name for. Continuous growth keeps the trajectory perfectly in sync with your current amount.

Read the article on e for more details (e is a special number, like pi, and is roughly 2.718). If we have rate r and time t (in years), the result is:

![]()

If you have a 50% APR, it would be an APY of $e^(.50)$ = 64.9% if compounded continuously. That’s a pretty big difference! Notice that e takes care of the icky parts, like dividing by an infinite number of periods.

Why’s this useful?

- Most natural phenomena grow continuously. As mentioned earlier, physical phenomena grows on its own schedule: radioactive material doesn’t wait for the Earth to go around the Sun before deciding to decay. Any physical equation that models change is going to use $e^rt$.

- $e^rt$ is the adjustable, one-size-fits-all exponential. It sounds strange, but e can even model the jumpy, staircase-like growth we’ve seen with compound interest. We’ll get into this in a later article.

Most interest discussions leave e out, as continuous interest is not often used in financial calculations. (Daily compounding, $(1 + r/365)^365$, is generous enough for your bank account, thank you very much. But seriously, daily compounding is a pretty good approximation of continuous growth.)

The exponential e is the bridge from our jumpy “delayed” growth to the smooth changes of the natural world.

A Few Examples

Let’s try a few examples to make sure it’s sunk in. Remember: the APR is the rate they give you, the APY is what you actually earn (your true return).

- Is a 4.5 APY better than a 4.4 APR, compounded quarterly? You need to compare APY to APY. 4.4% compounded quarterly is $(1 + 4.4\%/4)^4 = 4.47% $, so the 4.5% APY is still better.

- Should I pay my mortgage at the end of the month, or the beginning? The beginning, for sure. This way you knock out a chunk of debt early, preventing that “debt factory” from earning interest for 30 days. Suppose your loan APY is 6% and your monthly payment is \$2000. By paying at the start of the month, you’d save \$2000 * 6% = \$120/year, or \$3600 throughout a 30-year mortgage. And a few grand is nothing to sneeze at.

- Should I use several small payments, or one large payment?. You want to pay debt off as early as possible. \$500/week for 4 weeks is better than \$2000 at the end of the month. Each payment stops a few weeks’ worth of interest. The math is a bit tricker, but think of it as 4 \$500 investments, each getting different return. In a month, the first payment saves 3 week’s worth of interest: $500 * (1 + daily rate)^21$. The next saves 2 weeks: $500 * (1 + daily rate)^14$. The third saves a week $500 * (1 + daily rate)^7$ and the last payment doesn’t save any interest. Regardless of the details, prepayment will save you money.

The general principle: When investing, get interest paid early, so it can compound. When borrowing, pay debt early to prevent that interest from compounding.

Onward and Upward

This is a lot for one sitting, but I hope you’ve seen the big picture:

- The interest rate (APR) is the “speed” at which money grows.

- Compounding lets you adjust your “speed” as you earn more interest. The APR is the initial speed; the APY is the actual change during the year.

- Man-made growth uses $(1+r)^n$, or some variant. We like our loans to line up with years.

- Nature uses $e^{rt}$. The universe doesn’t particularly care for our solar calendar.

- Interest rates are tricky. When in doubt, ask for the APY and pay debt early.

Treating interest in this funky way (trajectories and factories) will help us understand some of e’s cooler properties, which come in handy for calculus. Also, try the Rule of 72 for a quick way to compute the effect of interest rates mentally (that investment with 6% APY will double in 12 years). Happy math.

Other Posts In This Series

- An Intuitive Guide To Exponential Functions & e

- Demystifying the Natural Logarithm (ln)

- A Visual Guide to Simple, Compound and Continuous Interest Rates

- Common Definitions of e (Colorized)

- Understanding Exponents (Why does 0^0 = 1?)

- Using Logarithms in the Real World

- How To Think With Exponents And Logarithms

- Understanding Discrete vs. Continuous Growth

- What does an exponent really mean?

- Q: Why is e special? (2.718..., not 2, 3.7 or another number?)