The Pythagorean theorem can apply to any shape, not just triangles. It can measure nearly any type of distance. And yet this 2000-year-old formula is still showing us new tricks.

Re-arranging the formula from this:

![]()

to this:

![]()

helps us understand the relationship between slope (steepness) and distance. Let’s take a look.

Rescale Your Triangle

Scaling leads to new insights. Yes, \$500k/year is a lot; but it really comes alive when you imagine things costing 10x less (A new laptop? \$150. A new porsche? \$6000).

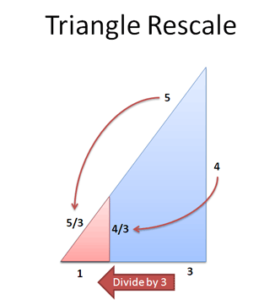

Rescaling formulas can be eye-opening as well. Let’s start with our favorite 3-4-5 triangle and divide every side by 3:

What happened?

Well, we have a smaller red triangle with sides 3/3 (aka 1), 4/3 and 5/3. We’ve got a mini version of the large triangle, and the Pythagorean Theorem still holds:

![]()

So Why’s This Special?

It doesn’t seem like much, but there’s some surprising insights:

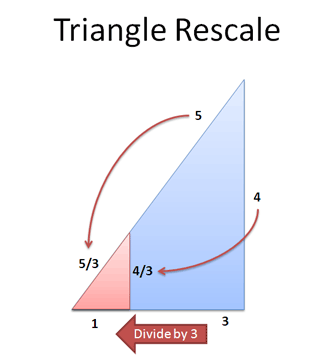

First, we can rescale any triangle to have 1 as the smallest side (divide by “a”). All similar triangles (i.e. those with the same ratios, like 3-4-5 and 6-8-10) will shrink into the same mini triangle.

This mini triangle has an interesting property: it only cares about the ratio b/a. The only “meaningful” numbers are 1 and (b/a), giving:

![]()

And what’s special about b/a? It’s the slope of the hypotenuse line! It’s called the slope, the gradient, the derivative, rise over run — whatever the label, b/a is the rate at which the hypotenuse changes!

This makes sense. For every unit traveled along the short leg, we gain “slope units (b/a)” on the other leg. In a 3-4-5 triangle, we go 4/3 units “North” for every 1 unit “East”. And the length of our hypotenuse increases 5/3 (1.66) for every 1 unit East.

The result is pretty cool: we used the steepness of the hypotenuse (b/a) to find the distance traveled per unit East, $\sqrt{1 + (b/a)^2}$.

An Example, Please

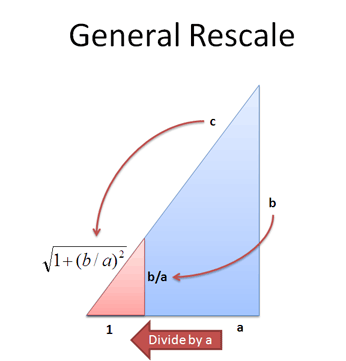

This is a bit weird, so let’s do an example. Suppose we’ve gone 5 units East and 12 units North. What’s our distance from the starting point?

The traditional approach plugs in the Pythagorean Theorem to get $c = \sqrt{5^2 + 12^2} = 13$. It works, but let’s try our mini-triangle method:

Instead of a large triangle with sides 5 and 12, scale down by 5: we get a mini triangle with sides 5/5 (or 1) and 12/5. The “mini hypotenuse” is then $\sqrt{1 + (12/5)^2} = 2.6$. This means we travel 2.6 units along the hypotenuse for every 1 unit East. Going the full 5 units East (our original triangle) is 5 * 2.6 = 13 units. Neato — we got the same answer both ways.

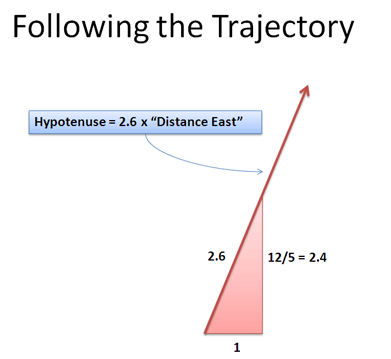

But silly me, I made a mistake. Instead of 5 units on that trajectory, I meant 6. No 7. No wait, 8. 9, for sure.

Normally, we’d be furiously hammering that square root button to find the new distance. Maybe even using trigonometry to “make it easier”. But not today — since we’re on the same trajectory, we can re-use our scaling constant of 2.6:

We can find the new distance traveled with regular multiplication, with nary a square root in sight. Cool! This approach is faster for humans and computers alike — you wouldn’t believe the crazy approaches programmers take to avoid a square root.

Static and Dynamic Formulas

I’ve realized that our venerable Pythagorean Theorem focuses on a and b separately:

![]()

We consider a and b as separate elements, to be squared and summed. This approach is straightforward, and helps when designing bridges or making pictures of triangles. The traditional formula focuses on final values.

But the rescaled version has a new twist:

![]()

We’re not that interested in the separate quantities — we want the ratio b/a, or the slope of the hypotenuse. This slope creates a scaling constant, $\sqrt{1 + (b/a)^2}$, that tells us how our “Eastward” motion translates to distance along our path. The dynamic formula focuses on rates of change.

If we have a hypothetical function f(x), we might write the dynamic Pythagorean Theorem this way:

![]()

This concept is used in calculus to find the length of any line or curve — but we’ll save that for another day.

The key is to realize a single formula can be re-arranged and lead to new insights. Stay curious — we stop learning when we think we’ve “got it all figured out”.

Appendix 1: Slope vs. Distance

One point that confused me was separating the idea of slope (b/a) from distance traveled (the hypotenuse, c).

Slope is b/a, rise over run — how much height you get when you increase width. How “steep” the hill is, so to speak. Unfortunately, the word “slope” makes us think of the side of the hill — but slope is really about height.

Distance (the hypotenuse) is about the side of the hill — how far you’ve walked. The “steepness” isn’t that important — you’re laying a measuring tape on the ground, which could be flat, vertical or upside-down. Does the length of a board depend on how you hold it?

But, in our man-made world, slope and distance are related because we often express locations in terms of “units East (x coordinate)” and not “units along a path”. So when a map says “go 1 mile due East” and you’re in front a mountain (large slope), you end up traveling a large distance (more than 1 mile). When on a flat road (zero slope), 1 mile East is simply 1 mile East. The bigger the slope, the more distance you must travel to “go 1 mile East”.

Again, we see that the Pythagorean Theorem is not just about triangles — it can convert slope (steepness) into distance traveled. Happy math.