Everyone’s heard of the stock market — but few know why it works. Were you aware that each stock has two prices? That you can’t buy and sell for the same amount? That a “stock market” works better and is more open than a “stock store”?

If you’re like most of us, probably not. Here’s why stock markets rock:

- They match buyers and sellers efficiently

- All prices are transparent and you see what other people have paid/sold for

- You name your own price and get that price if there’s a willing partner

Most explanations jump into the minor details — not here. Today we’ll see why the stock market works as it does.

iPhones Ahoy!

I’m told iPhones are popular with the 18-35 demographic. A market research firm asked me to find a good selling price, so I’ll pass the question onto you:

Me: You, the coveted 18-35 year old demographic, want an iPhone. What’s it worth?

You: Dude, just get the price. Duh.

Ok hotshot, riddle me this: what is the price, exactly?

- What you can buy it for? (Your best bid)

- What you can sell it for? (What you’d ask for it)

So which price is the “real one”? Both.

You see, buyers and sellers each have prices in mind. When prices match, whablamo, there’s a transaction (no match, no whablamo).

The idea of two prices for every item is key to understanding any market, not just stocks. Everything has a bid and an ask, and each shopping model has a different way of handling them. This leads to different advantages for buyers and sellers.

Shopping Time

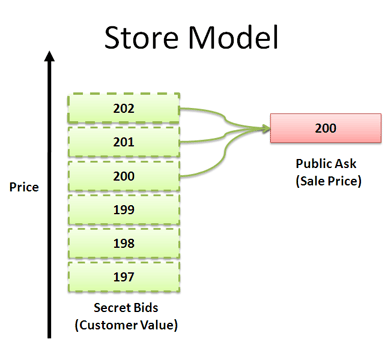

Suppose we want to buy an iPhone from Amazon. You see the selling price of \$200 (Amazon’s ask), and personally decide if it’s worth it (i.e. less than or equal to your bid):

In the store model, Amazon shows a public asking price (\$200). Each buyer has a secret bidding price, some more than others. Buyers willing to bid \$200 or more purchase it; the rest hold off (\$199 and below).

Amazon picks a price that attracts the most bidders yet still keeps a profit. In the store model:

- Buyer pro: Buyers know the price and can pay less than their internal value

- Buyer con: Buyers have to visit multiple stores to find the best price

- Seller con: Sellers don’t know what each buyer is willing to pay; it’s difficult to set the pricing. Do low sales mean a bad price or a bad product?

Even though buyers are “in control”, they may have to search around to find a store that meets their bid (if any). That’s inefficient.

Onto eBay

Now suppose we want to sell our new, unopened gadget (you, the 18-35 demographic, are fickle like that; the survey said so). Sure, we could try to sell it on Amazon — now we’re our own store and need a price we think people will pay. We’re in the same boat as Amazon, and could set the price too low. That’s no fun.

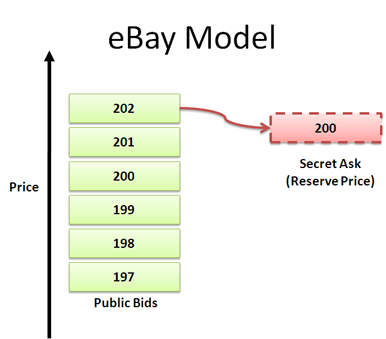

Instead, we auction off the new iPhone on eBay to maximize profits:

In the eBay model, buyers have public bids and compete for the product. The seller keeps their minimum price secret and hopes to make a profit by having someone “overpay”. In the auction model:

- Seller pro: Sellers have a secret ask (reserve or minimum price) and can get paid above this.

- Seller pro: Buyers’ demand is transparent. They can easily see if they are pricing too high.

- Buyer con: Difficult to buy a product.

eBay is great for sellers — you have the chance of making extra profit. For buyers, it’s not so great: you can lose auctions by \$1 (paying 201 when 202 was the highest bid), even though the seller would have been happy with 201. You could enter multiple auctions with \$201 but risk getting two iPhones.

Want Ads and Hagglers

There’s other trading approaches also:

- Want ad: Publicly announce your desire for an iPhone and let sellers fight it out.

- Haggle: Find someone with an iPhone, and without knowing a selling price, make an offer. You both haggle back and forth, trying to eke the other person out of a few bucks. If you’ve gone car shopping you know how fun this is.

In want ads, the asks are transparent while the bids (your value) are hidden. When haggling, both prices are hidden which can lead to a stressful situation.

It’s About Supply and Demand

Each model has similar concepts, namely:

- Supply: sellers provide asks

- Demand: buyers provide bids

The phrase liquidity refers to how effectively you can trade; how easily cash can flow. When buyers and sellers have to argue or haggle, trading freezes up. In particular, there’s a common problem in the market above:

- There’s secret prices and a lack of transparency

- There’s multiple vendors and a lack of consolidation

When buyers and sellers need to search to find each other, and haggle when they get there, trading slows down.

Enter the Market

But hope is not lost! Surprisingly, the very symbol of capitalism is an “open source” model:

- All prices are transparent

- Buyers write public bids (buying price)

- Sellers write public asks (selling price)

- There’s one location to get a particular stock; there’s no searching

- Dealers/specialists help match buyers and sellers

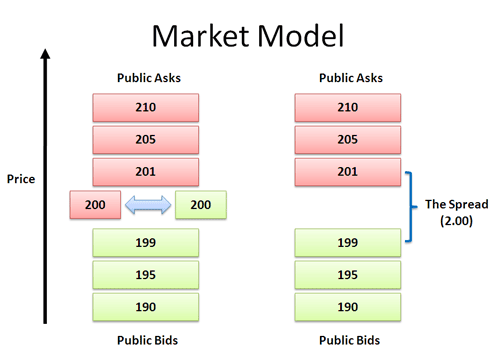

And here’s what it looks like:

Every iPhone seller lists their asking price (210, 205, 201, 200). Every iPhone buyer lists their buying price (190, 195, 199, 200). When prices match, a transaction happens: the buyer who wants to pay 200 gets matched with the seller who wants 200. They’re happy.

Eventually the matches cease and we come to a standstill.

Drop and Spread ‘em.

Trades don’t last forever: there’s a standoff and an awkward pause. The lowest sellers want \$201, and the highest bidder wants \$199; this \$2 gap is called the spread. The last price of a transaction was \$200.

Now what happens? Buyers and sellers can do:

- Limit order: put their bid/ask in the queue.

- Market order: buy or sell immediately.

When you place a limit order (“Buy an iPhone for 195″), your order gets added to the bid queue (similar for asks).

If you need to trade right now (“buy it now!” or “sell it now!”), then you use a market order. You’ll get the best price available:

- Market order to sell: You can unload your iPhone for \$199 (the highest bid). The “last” price is now 199.

- Market order to buy: You can buy for \$201 (the lowest price). The “last” price is now 201.

Now this is interesting. Notice how market orders take items off the queue and change the last price. When people place market orders, the stock price fluctuates. Yes, it’s “just” supply and demand, but it’s pretty cool to know it’s happening real-time in the stock market.

If there’s a lot of buyers, they’ll “use up” the ask queue and the price will rise. If there’s a lot of sellers, they’ll “use up” the bid queue and the price will fall.

This explains why it’s hard to buy and sell for the same price. If you buy for 201, and no new bids come in, you’ll only be able to sell for 199.

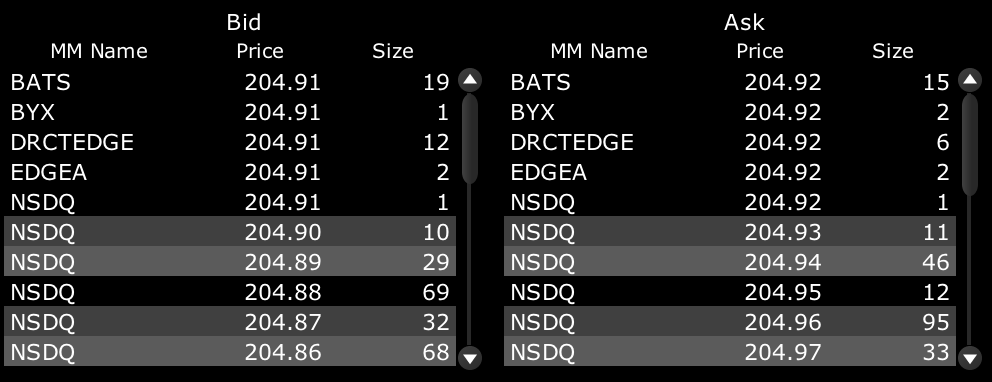

In the real world, the list looks like this:

You see the bids, asks, quantities, and names. Here the bid is 204.91 (max someone will pay) and the ask is 204.92 (min someone will sell). When a buyer or seller gets restless, they may decide to immediately buy/sell, which moves the price. This detailed data is called a Level II quote.

So Who Runs This Popsicle Stand?

The NYSE and NASDAQ are the two major American exchanges. There are differences, but at the core they provide:

- A single market to trade. Originally, all stocks for Microsoft (MSFT), were supposed to be traded on the NASDAQ exchange, and all stocks for Ford (F) on the NYSE. However, there were multiple smaller exchanges ("stores"), and hey -- sometimes trades happened. In 2005, the Regulation National Market System required exchanges to provide the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO) to get the best price across all exchanges. It's like built-in best-price guarantee when shopping. So, we trade stocks on a single "national" market.

- A market maker or “specialist” (not the kind that kills people). These people make the market liquid: they help collect and match bids and asks. The NYSE has one specialst per stock; NASDAQ has several market makers (dealers) who compete on price.

How Do They Make Money?

Well, often they don’t. In the NYSE, 88% of the trades happen between the public without needing the specialist (remember those guys waving papers and screaming at each other? I wouldn’t want to get involved with them either).

But sometimes they are needed. The market makers literally “create a market” by providing liquidity: they must always offer stocks for you to buy from them, or sell to them. With many market makers competing for your business, popular stocks get a narrower spread.

But how do market makers make money?

Well, it’s a bit like a currency exchange at a bank, where’s there’s a different rate for buying and selling. If a steady stream of buyers and sellers transacts at the booth, the exchange pockets the price difference.

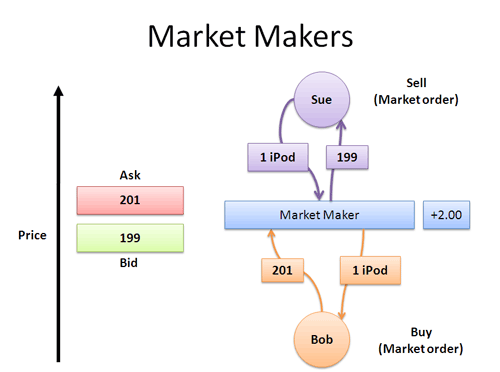

Let’s say Sue has an iPhone to sell, and Bob wants to buy an iPhone. They both want to make an immediate (market) order that's guaranteed to execute. It might go like this:

- Sue wants to sell her phone, right now. The market maker looks at the buying current price (198), and offers something slightly better. "Hey Sue, I’ll take your iPhone. Here’s 199. The others are only bidding 198."

- Bob wants to buy a phone, right now. The market maker looks at the current selling price (202), and lists a price that's slightly better. "Hey Bob, I'll sell you a phone for 201. The others are asking 202 for it."

See what happened? The market maker bought an iPhone for 199 and sold it for 201: they pocketed the spread of \$2. However, Sue and Bob got better prices than they would have otherwise.

Market makers are just another market participant, but they are obligated to always list their bid and ask price. But, they are taking some risk: in a volatile market, they may pick up too many shares that they can't sell later. Then, they'd "widen the spread" by listing prices that would help guarantee a profit: perhaps offering to buy at 195 and sell at 205, expecting a steady stream of market orders.

As a regular investor, you can avoid paying the spread by only putting in limit orders. But you aren't guaranteed to make a trade.

It’s All About Timing

Bill Gates has a lot of shares of Microsoft. People naively put this wealth as “shares times price”, but you know that doesn’t really work. If he tried to sell all his shares, he’d use up the bids.

Each block of shares would be sold for a lower and lower value — and potential buyers would panic and reduce their bids, thinking something was amiss. Sellers would fear the worst and lower their asks to compete. Pandemonium would ensue. So the actual liquidation value of his shares is really some fraction of the reported amount. But it’s still nothing to sneeze at.

Similarly, large institutions must spread their stock trades over time so they don’t disrupt the market (and evaporate their profits).

The market has built-in shock absorbers: as you sell more, the price you get is smaller and smaller, so you sell less. As you buy more, the price you pay gets higher and higher, so you buy less. So it makes sense to take things slow. Nifty.

There’s Much to Learn

I’ve simplified a lot of things and only scratched the glossed-over surface. Each market has its own rules to create a trading-friendly environment. Read more here:

- Invest-faq on the NASDAQ and NYSE. The NYSE is an “auction market” where bids and asks are public (this is different from eBay auctions, where only bidders compete in a given auction). The NASDAQ is a “dealer market” where you buy/sell from a dealer’s personal inventory.

- Investopedia on the difference between a market maker and specialist

- See the current bid/ask for Microsoft or Google (and # of shares at that price)

But, my goal wasn’t to fill your head with details. I want to share insight:

- Markets exist to match supply and demand

- The stock market is fast, transparent, and efficient

- Every stock has a bid and ask

- Buying or selling changes the trading price in a direct, measurable way

Want a stock tip? Don’t listen to stock tips. (Stolen from a Charles Schwab ad.) This article is about looking at a system as one way to solve the larger problem of trading goods. Happy investing.