I’m glad people liked the introduction to Rails; now you scallawags get to avoid my headaches with the model-view-controller (MVC) pattern. This isn’t quite an intro to MVC, it’s a list of gotchas as you plod through MVC the first few times.

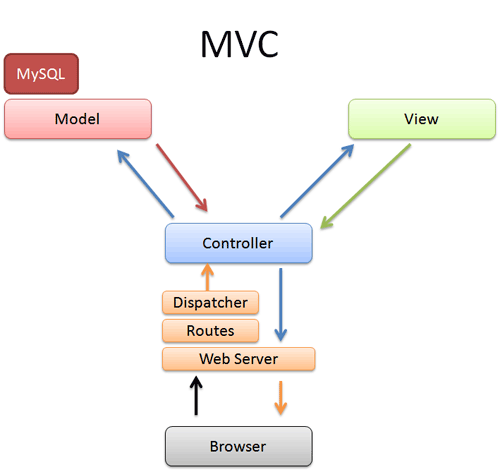

Here’s the big picture as I understand it:

The browser makes a request, such as http://mysite.com/video/show/15

The web server (mongrel, WEBrick, etc.) receives the request. It uses routes to find out which controller to use: the default route pattern is “/controller/action/id” as defined in

config/routes.rb. In our case, it’s the “video” controller, method “show”, with the id parameter set to “15″. The web server then uses the dispatcher to create a new controller, call the action and pass the parameters.Controllers do the work of parsing user requests, data submissions, cookies, sessions and the “browser stuff”. They’re the pointy-haired manager that orders employees around. The best controller is Dilbert-esque: It gives orders without knowing (or caring) how it gets done. In our case, the show method in the video controller knows it needs to lookup a video. It asks the model to get video 15, and will eventually display it to the user.

Models are Ruby classes. They talk to the database, store and validate data, perform the business logic and otherwise do the heavy lifting. They’re the chubby guy in the back room crunching the numbers. In this case, the model retrieves video 15 from the database.

Views are what the user sees: HTML, CSS, XML, Javascript, JSON. They’re the sales rep putting up flyers and collecting surveys, at the manager’s direction. Views are merely puppets reading what the controller gives them. They don’t know what happens in the back room. In our example, the controller gives video 15 to the “show” view. The show view generates the HTML: divs, tables, text, descriptions, footers, etc.

The controller returns the response body (HTML, XML, etc.) & metadata (caching headers, redirects) to the server. The server combines the raw data into a proper HTTP response and sends it to the user.

It’s more fun to imagine a story with “fat model, skinny controller” instead of a sterile “3-tiered architecture”. Models do the grunt work, views are the happy face, and controllers are the masterminds behind it all.

Many MVC discussions ignore the role of the web server. However, it’s important to mention how the controller magically gets created and passed user information. The web server is the invisible gateway, shuttling data back and forth: users never interact with the controller directly.

SuperModels

Models are fat in Railsville: they do the heavy lifting so the controller stays lean, mean, and ignorant of the details. Here’s a few model tips:

Using ActiveRecord

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

end

The code < ActiveRecord::Base means your lowly User model inherits from class ActiveRecord::Base, and gets Rails magic to query and save to a database.

Ruby can also handle “undefined” methods with ease. ActiveRecord allows methods like “find_by_login”, which don’t actually exist. When you call “find_by_login”, Rails handles the “undefined method” call and searches for the “login” field. Assuming the field is in your database, the model will do a query based on the “login” field. There’s no configuration glue required.

Defining Class and Instance Methods

def self.foo

"Class method" # User.foo

end

def bar

"instance method" # user.bar

end

Class and instance methods can cause confusion.

user (lowercase u) is an object, and you call instance methods like user.save.

User (capital U) is a class method – you don’t need an object to call it (like User.find). ActiveRecord adds both instance and class methods to your model.

As a tip, define class methods like User.find_latest rather than explicitly passing search conditions to User.find (thin controllers are better).

Using Attributes

Regular Ruby objects can define attributes like this:

# attribute in regular Ruby

attr_accessor :name # like @name

def name=(val) # custom setter method

@name = val.capitalize # clean it up before saving

end

def name # custom getter

"Dearest " + @name # make it nice

end

Here’s the deal:

- attr_accessor :name creates get and set methods (name= and name) on your model. It’s like having a public instance variable

@name. - Define method

name=(val)to change how @name is saved (such as validating input). - Define method

nameto control how the variable is output (such as changing formatting).

In Rails, attributes can be confusing because of the database magic. Here’s the deal:

- ActiveRecord grabs the database fields and throws them in an

attributesarray. It makes default getters and setters, but you need to calluser.saveto save them. If you want to override the default getter and setter, use this:

# ActiveRecord: override how we access field def length=(minutes) self[:length] = minutes * 60 end def length self[:length] / 60 end

ActiveRecord defines a “[]” method to access the raw attributes (wraps the write_attribute and read_attribute). This is how you change the raw data. You can’t redefine length using

def length # this is bad

length / 60

end

because it’s an infinite loop (and that’s no fun). So self[] it is. This was a particularly frustrating Rails headache of mine – when in doubt, use self[:field].

Never forget you’re using a database

Rails is clean. So clean, you forget you’re using a database. Don’t.

Save your models. If you make a change, save it. It’s very easy to forget this critical step. You can also use update_attributes(params) and pass a hash of key -> value pairs.

Reload your models after changes. Suppose a user has_many videos. You create a new video, point it at the right user, and call user.videos to get a list. Will it work?

Probably not. If you already queried for videos, user.videos may have stale data. You need to call user.reload to get a fresh query. Be careful — the model in memory acts like a cache that can get stale.

Making New Models

There’s two ways to create new objects:

joe = User.new( :name => "Sad Joe" ) # not saved

bob = User.create ( :name => "Happy Bob" ) # saved

User.newmakes a new object, setting attributes with a hash.newdoes not save to the database: you must calluser.saveexplicitly. Methodsavecan fail if the model is not valid.User.createmakes a new model and saves it to the database. Validation can fail;user.errorsis a hash of the fields with errors and the detailed message.

Notice how the hash is passed. With Ruby’s brace magic, {} is not explicitly needed so

user = User.new( :name => "kalid", :site => "instacalc.com" )

becomes

User.new( {:name => "kalid", :site => "instacalc.com"} )

The arrow (=>) implies that a hash is being passed.

Using Associations

Quick quiz, hotshot: suppose users have a “status”: active, inactive, pensive, etc. What’s the right association?

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

belongs_to :status # this?

has_one :status # or this?

end

Hrm. Most likely, you want belongs_to :status. Yeah, it sounds weird. Don’t think about the phrase “has_one” and “belongs_to”, consider the meaning:

- belongs_to: links_to another table. Each user references (links to) a status.

- has_one: linked_from another table. A status is linked_from a user. In fact, statuses don’t even know about users – there’s no mention of a “user” in the statuses table at all. Inside class Status we’d write

has_many :users(has_one and has_many are the same thing – has_one only returns 1 object that links_to this one).

A mnemonic:

- “belongs_to” rhymes with “links_to”

- “has_one” rhymes with “linked_from”

Well, they sort of rhyme. Work with me here, I’m trying to help.

These associations actually define methods used to lookup items of the other class. For example, “user belongs_to status” means that user.status queries the Status for the proper status_id. Also, “status has_many :users” means that status.users queries the user table for everyone with the current status_id. ActiveRecord handles the magic once we declare the relationship.

Using Custom Associations

Suppose I need two statuses, primary and secondary? Use this:

belongs_to :primary_status, :model => 'Status', :foreign_key => 'primary_status_id'

belongs_to :secondary_status, :model => 'Status', :foreign_key => 'secondary_status_id'

You define a new field, and explicitly reference the model and foreign key to use for lookups. For example, user.primary_status returns a Status object with the id of “primary_status_id”. Very nice.

Quick Controllers

This section is short, because controllers shouldn’t do much besides boss the model and view around. They typically:

- Handle things like sessions, logins/authorization, filters, redirection, and errors.

- Have default methods (added by ActionController). Visiting

http://localhost:3000/user/showwill attempt to call the “show” action if there is one, or automatically render show.rhtml if the action is not defined. - Pass instance variables like @user get passed to the view. Local variables (those without @) don’t get passed.

- Are hard to debug. Use

render :text => "Error found" and returnto do printf-style debugging in your page. This is another good reason to put code in models, which are easy to debug from the console. - Use sessions to store data between requests: session[:variable] = “data”.

I’ll say it again because it’s burned me before: use @foo (not “foo”) to pass data to the view.

Using Views

Views are straightforward. The basics:

- Controller actions use views with the same name (method

showloadsshow.rhtmlby default) - Controller instance variables (@foo) are available in all views and partials (wow!)

Run code in a view using ERB:

<% ... %>: Run the code, but don’t print anything. Used for if/then/else/end and array.each loops. You can comment out sections of HTML using <% if false %> Hi there <% end %>. You get a free blank line, since you probably have a newline after the closing %>.<%- ... %>: Run the code, and don’t print the trailing newline. Use this when generating XML or JSON when breaking up .rhtml code blocks for your readability, but don’t want newlines in the output.<%= ... %>: Run the code and print the return value, for example: <%= @foo %> (You did remember the @ sign for controller variables passed to the view, right?). Don’t putifstatements inside the<%=, you’ll get an error.<%= h ... %>: Print the code and html escape the output:>becomes>. h() is actually a Ruby function, but called without parens, as Rubyists are apt to do.

It’s a bit confusing when you start out — run some experiments in a dummy view page.

Take a breather

The MVC pattern is a lot to digest in one sitting. As you become familiar with it, any Rails program becomes easy to dissect: it’s clear how the pieces fit together. MVC keeps your code nice and modular, great for debugging and maintenance.

In future articles I’ll discuss the inner details of MVC and how Rails forms work (another headache of mine). If you want a jumpstart on the nitty gritty, browse the Rails source and try to follow the path of a request:

- WEBrick server modified to call the Rails routing library and dispatcher.

- Rails Dispatcher actually creates the controller and passes it data.

- ActionController Base defines many functions, including those to call a controller action (using appropriate defaults), render text, and return a response.

But all in good time my friends — I’ll explain it as I understand it. And if you had any forehead-slapping moments with MVC, drop me a note below.