Math class has two goals:

- Verify that a statement is true

- Understand why a statement is true

There's a tendency to put the goals in opposition, assuming concepts are either "easily understood but wrong" or "difficult to understand yet correct".

It's like a restaurant that believes in having taste or nutrition, but not both. Why choose?

Our goal is a deep intuition for correct things. And it's ok to start with an understood "sorta-true" concept and refine it to an understood "very-true" version:

Correctness isn't binary. Our standards for a valid proof have evolved over the years, and in a century our notion of what's true may seem embarrassingly primitive. That's ok: let's get a decent understanding and work to make it better.

We have to balance two roles: the safety inspector who makes sure the food is safe, and the customer who wants to enjoy the meal. In my head I think about "inspection mode" and "tasting mode": the secret is inspecting things that already taste good.

Example: The Pythagorean Theorem

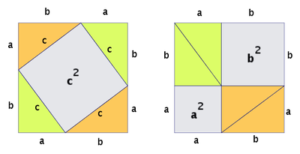

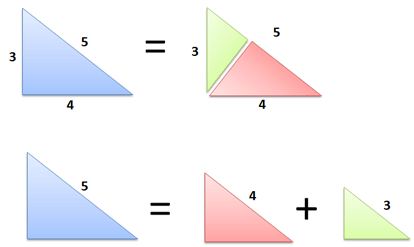

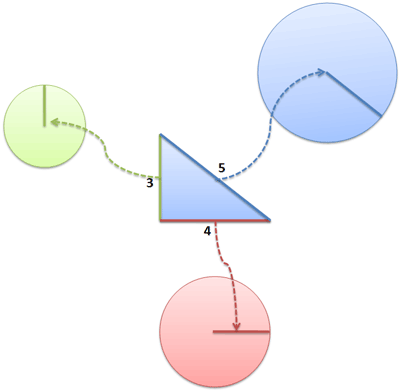

The Pythagorean theorem is usually introduced as a statement about triangles. A common proof is a visual rearrangement, like this:

This is nutritious and correct, but not tasty to me. It seems like a special case, an optical illusion: with just the right shape, things can be re-arranged.

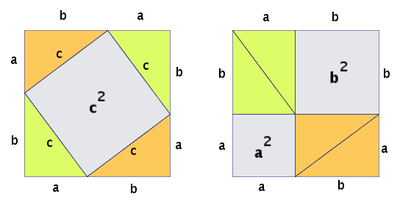

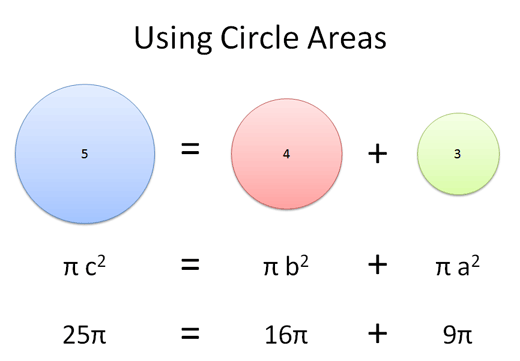

A tastier proof is that the Pythagorean Theorem is really about the nature of 2d area. A big shape, when split, yields two smaller shapes. The total area must be the same:

The split-apart area can come from a triangle, circle, or cardboard cutout of Thomas Jefferson. It doesn't matter: two pieces, when cut from a larger one, must have the same total area.

Aha!

This intuition can then be refined into a more formal statement.

Example: Euler's Formula

Here's a trickier example: Euler's Formula.

![]()

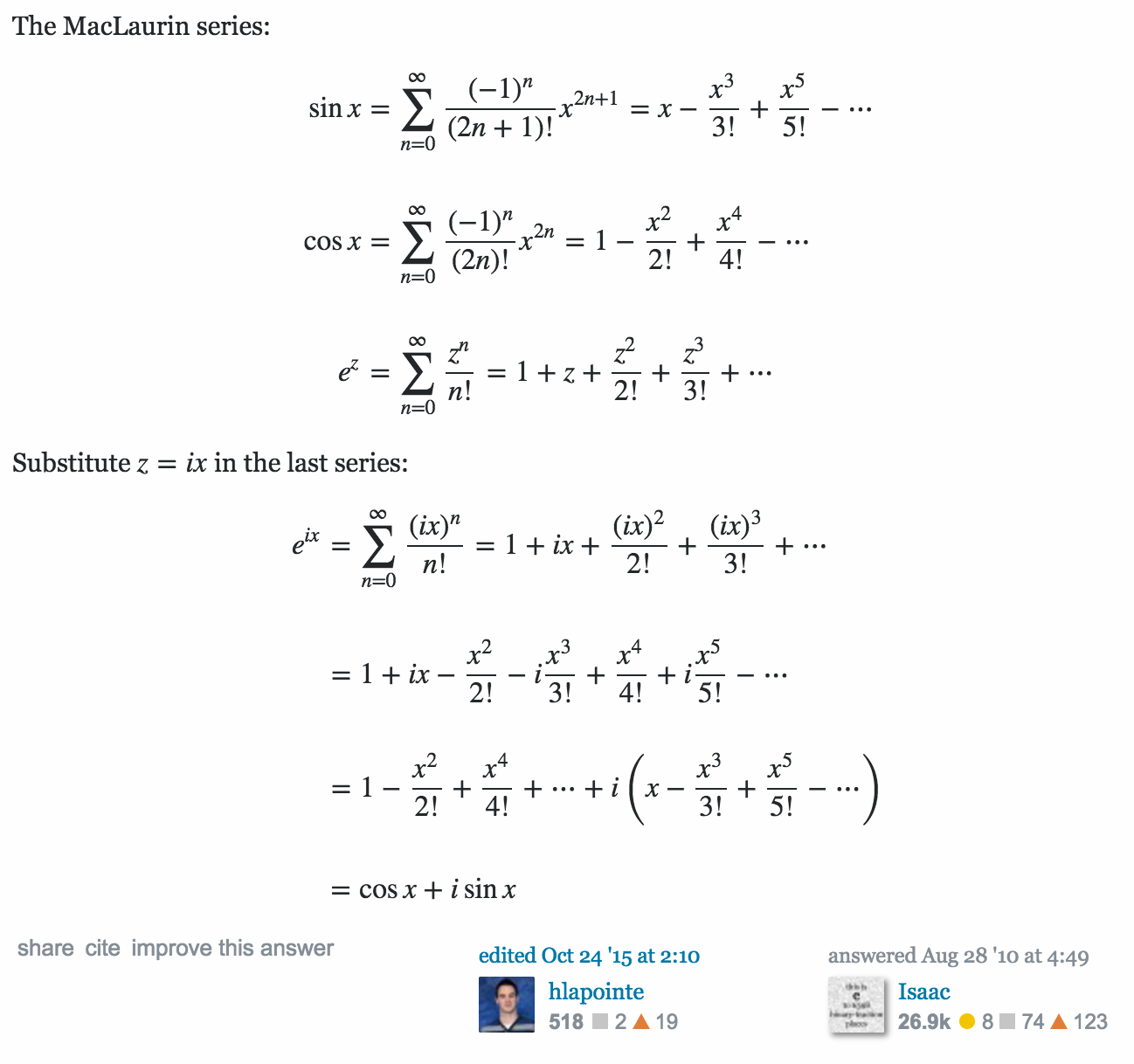

It's a baffling statement, and here's the common justification:

It's crisp and concise, but unsatisfying to even other math fans:

I agree: it's a bunch of symbols that happen to line up. Here's a tastier version:

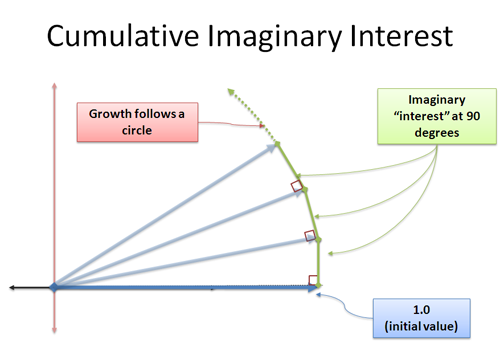

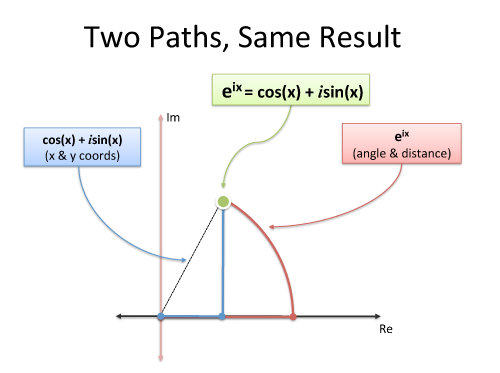

- $e^x$ represents continuous growth (interest earning interest, which earns interest…)

- $\sin(x)$ and $\cos(x)$ represent vertical and horizontal directions

- $i$ represents rotation

If we create "continuous rotation" ($e^{ix}$) then we move in a circle, which can be separated into horizontal and vertical components ($\cos(x)$ and $i \sin(x)$).

Again, this intuition can be sharpened further:

- $e^x$ can be seen as an infinite series, starting with an initial value ($1$), the interest it earns ($x$), the interest that earns ($\frac{x^2}{2!}$), and so on.

- Sine (and cosine) are infinite series based on an initial impulse, which creates a restoring force, which creates a restoring force, and so on. This is like interest that earns interest in the opposite direction (and why sine oscillates without going to infinity: its motion opposes itself.)

- Plugging $i$ into $e^x$ means we earn "imaginary interest" ($i$), which earns "imaginary imaginary interest" ($-1$) which earns "imaginary imaginary imaginary interest" ($-i$), and so on. Some of the interest opposes the previous terms, and we can collect them into patterns matching sine and cosine.

Rather than staring at a dry proof and trying to understand it directly, get a rough intuition (ADEPT method) and then see if the proof makes sense. It's a bit of math inception, where we try to understand the verification step, not simply verify the verification step.

Happy math.

Appendix: On Proof and Progress in Mathematics

William Thurston (Fields Medal Winner) wrote a great essay, On Proof and Progress in Mathematics. It's full of ideas I found interesting:

- The question for mathematicians is: "How do mathematicians advance human understanding of mathematics?"

For instance, when Appel and Haken completed a proof of the 4-color map theorem using a massive automatic computation, it evoked much controversy. I interpret the controversy as having little to do with doubt people had as to the veracity of the theorem or the correctness of the proof. Rather, it reflected a continuing desire for human understanding of a proof, in addition to knowledge that the theorem is true...They discover by this kind of experience that what they really want is usually not some collection of “answers”—what they want is understanding.

- We're never done explaining a concept:

We may think we know all there is to say about a certain subject, but new insights are around the corner. Furthermore, one person’s clear mental image is another person’s intimidation.

- On the role of intuition:

Personally, I put a lot of effort into “listening” to my intuitions and associations, and building them into metaphors and connections. This involves a kind of simultaneous quieting and focusing of my mind. Words, logic, and detailed pictures rattling around can inhibit intuitions and associations.

- The "emperor's clothes" problem in math happens even for professionals:

Nonetheless, most of the audience at an average colloquium talk gets little of value from it. Perhaps they are lost within the first 5 minutes, yet sit silently through the remaining 55 minutes. Or perhaps they quickly lose interest because the speaker plunges into technical details without presenting any reason to investigate them. At the end of the talk, the few mathematicians who are close to the field of the speaker ask a question or two to avoid embarrassment.

A further issue is that people sometimes need or want an accepted and validated result not in order to learn it, but so that they can quote it and rely on it.

- On the difference between everyday explanations and and technical ones:

Why is there such a big expansion from the informal discussion to the talk to the paper? One-on-one, people use wide channels of communication that go far beyond formal mathematical language. They use gestures, they draw pictures and diagrams, they make sound effects and use body language...In papers, people are still more formal. Writers translate their ideas into symbols and logic, and readers try to translate back.

It’s like a new toaster that comes with a 16-page manual. If you already understand toasters and if the toaster looks like previous toasters you’ve encountered, you might just plug it in and see if it works, rather than first reading all the details in the manual.

- On what motivates us to do math:

What motivates people to do mathematics? There is a real joy in doing mathematics, in learning ways of thinking that explain and organize and simplify. One can feel this joy discovering new mathematics, rediscovering old mathematics, learning a way of thinking from a person or text, or finding a new way to explain or to view an old mathematical structure.

I love the "aha!" moments when a concept click. People willing seek out mysteries and puzzles (movies where we don't know the ending, games like Tetris). Math is an experience with similar emotional payoffs when approached correctly.