Traditional version control helps you backup, track and synchronize files. Distributed version control makes it easy to share changes. Done right, you can get the best of both worlds: simple merging and centralized releases.

Distributed? What’s wrong with regular version control?

Nothing — read a visual guide to version control if you want a quick refresher. Sure, some people will deride you for using an “ancient” system. But you’re still OK in my book: using any VCS is a positive step forward for a project.

Centralized VCS emerged from the 1970s, when programmers had thin clients and admired “big iron” mainframes (how can you not like a machine with a then-gluttonous 8 bits to a byte?).

Centralized is simple, and what you’d first invent: a single place everyone can check in and check out. It’s like a library where you get to scribble in the books.

This model works for backup, undo and synchronization but isn’t great for merging and branching changes people make. As projects grow, you want to split features into chunks, developing and testing in isolation and slowly merging changes into the main line. In reality, branching is cumbersome, so new features may come as a giant checkin, making changes difficult to manage and untangle if they go awry.

Sure, merging is always “possible” in a centralized system, but it’s not easy: you often need to track the merge yourself to avoid making the same change twice. Distributed systems make branching and merging painless because they rely on it.

A Few Diagrams, Please

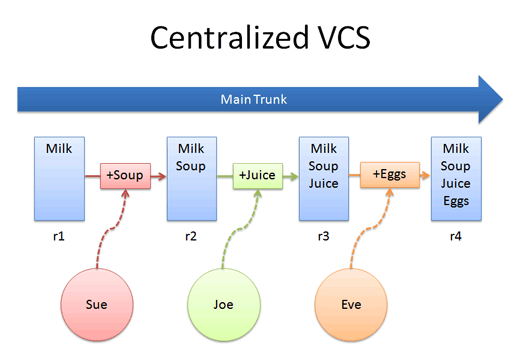

Other tutorials have plenty of nitty-gritty text commands; here’s a visual look. To refresh, developers use a central repo in a typical VCS:

Everyone syncs and checks into the main trunk: Sue adds soup, Joe adds juice, and Eve adds eggs.

Sue’s change must go into main before it can be seen by others. Yes, theoretically Sue could make a new branch for other people to try out her changes, but this is a pain in a regular VCS.

Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCS)

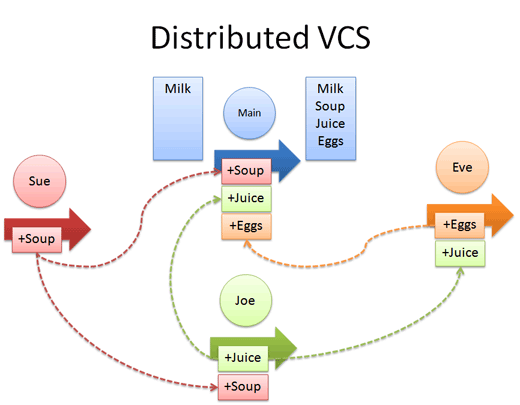

In a distributed model, every developer has their own repo. Sue’s changes live in her local repo, which she can share with Joe or Eve:

But will it be a circus with no ringleader? Nope. If desired, everyone can push changes into a common repo, suspiciously like the centralized model above. This franken-repo contains the changes of Sue, Joe and Eve.

I wish distributed version control had a different name, such as “independent”, “federated” or “peer-to-peer.” The term “distributed” evokes thoughts of distributed computing, where work is split among a grid of machines (like searching for signals with SETI@home or doing protein folding).

A DVCS is not like Seti@home: each node is completely independent and sharing is optional (in Seti you must phone back your results).

Key Concepts In 5 Minutes

Here’s the basics; there’s a book on patch theory if you’re interested.

Core Concepts

- Centralized version control focuses on synchronizing, tracking, and backing up files.

- Distributed version control focuses on sharing changes; every change has a guid or unique id.

- Recording/Downloading and applying a change are separate steps (in a centralized system, they happen together).

- Distributed systems have no forced structure. You can create “centrally administered” locations or keep everyone as peers.

New Terminology

- push: send a change to another repository (may require permission)

- pull: grab a change from a repository

Key Advantages

- Everyone has a local sandbox. You can make changes and roll back, all on your local machine. No more giant checkins; your incremental history is in your repo.

- It works offline. You only need to be online to share changes. Otherwise, you can happily stay on your local machine, checking in and undoing, no matter if the “server” is down or you’re on an airplane.

- It’s fast. Diffs, commits and reverts are all done locally. There’s no shaky network or server to ask for old revisions from a year ago.

- It handles changes well. Distributed version control systems were built around sharing changes. Every change has a guid which makes it easy to track.

- Branching and merging is easy. Because every developer “has their own branch”, every shared change is like reverse integration. But the guids make it easy to automatically combine changes and avoid duplicates.

- Less management. Distributed VCSes are easy to get running; there’s no “always-running” server software to install. Also, DVCSes may not require you to “add” new users; you just pick what URLs to pull from. This can avoid political headaches in large projects.

Key Disadvantages

- You still need a backup. Some claim your “backup” is the other machines that have your changes. I don’t buy it — what if they didn’t accept them all? What if they’re offline and you have new changes? With a DVCS, you still want a machine to push changes to “just in case”. (In Subversion, you usually dedicate a machine to store the main repo; do the same for a DVCS).

- There’s not really a “latest version”. If there’s no central location, you don’t immediately know whether to see Sue, Joe or Eve for the latest version. Again, a central location helps clarify what the latest “stable” release is.

- There aren’t really revision numbers. Every repo has its own revision numbers depending on the changes. Instead, people refer to change numbers: Pardon me, do you have change fa33e7b? (Remember, the id is an ugly guid). Thankfully, you can tag releases with meaningful names.

Mercurial Quickstart

Mercurial is a fast, simple DVCS. The nickname is hg, like the element Mercury.

cd project

hg init (create repo here)

hg add list.txt (start tracking file)

hg commit -m "Added file" (check file into local repo)

hg log (see history; notice guid)

changeset: 0:55bbcb7a4c24

user: Kalid@kazad-laptop

date: Sun Oct 14 21:36:18 2007 -0400

summary: Added file

[edit file]

hg revert list.txt (revert to previous version)

hg tag v1.0 (tag this version)

[edit file]

hg update -C v1.0 ("update" to the older tagged version; -C forces overwrite of local copy)

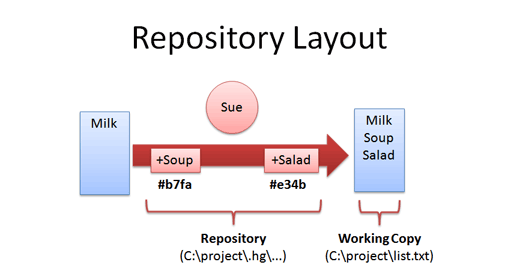

Once Mercurial has initialized a directory, it looks like this:

You have:

- A working copy. The files you are currently editing.

- A repository. A directory (.hg in Mercurial) containing all patches and metadata (comments, guids, dates, etc.). There’s no central server so the data stays with you.

In our distributed example, Sue, Joe and Eve have their own repos, with independent revision histories.

Understanding Updates and Merging

There’s a few items that confused me when learning about DVCS. First, updates happen in several steps:

- Getting the change into a repo (pushing or pulling)

- Applying the change to the files (update or merge)

- Saving the new version (commit)

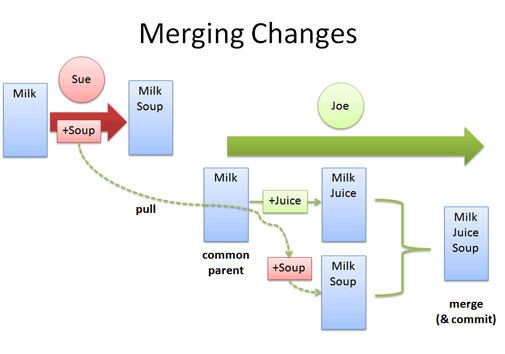

Second, depending on the change, you can update or merge:

- Updates happen when there’s no ambiguity. For example, I pull changes to a file that only you’ve been editing. The file just jumps to the latest revision, since there’s no overlapping changes.

- Merges are needed when we have conflicting changes. If we both edit a file, we end up with two “branches” (i.e. alternate universes). One world has my changes, the other world has yours. In this case we (probably) want to merge the changes together into a single universe.

I’m still wrapping my head around how easily branches spring up and collapse in a DVCS:

In this case, a merge is needed because (+Soup) and (+Juice) are changes to a common parent: the list with just “Milk”. After Joe merges the files, Sue can do a regular “pull and update” to get the combined file from Joe. She doesn’t have to merge again on her own.

In Mercurial you can run:

hg incoming ../another-dir (see pending changes)

hg pull ../another-dir (download changes)

hg update (actually apply changes...)

hg merge (... or merge if needed)

hg commit (check in merged file; unite branches)

Yep, the “pull-merge-commit” cycle is long. Luckily, Mercurial has shortcuts to combine commands into a single one. Though it seems complex, it’s much easier than handling merges manually in Subversion.

Most merges are automatic. When conflicts come up, they are typically resolved quickly. Mercurial keeps track of the parent/child relationship for every change (our merged list has two parents), as well as the “heads” or latest changes in each branch. Before the merge we have two heads; afterwards, one.

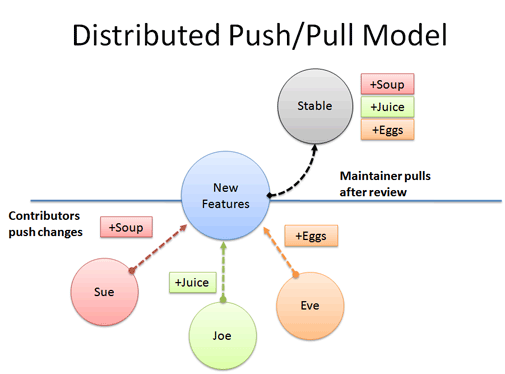

Organizing a Distributed Project

Here’s one way to organize a distributed project:

Sue, Joe and Eve check changes into a common branch. They can trade patches with each other to do simple “buddy builds”: Hey buddy, can you try out these patches? I need to see if it works before I push to the experimental branch.

Later, a maintainer can review and pull changes from the experimental branch into a stable branch, which has the latest release. A distributed VCS helps isolate changes but still provide the “single source” of a centralized system. There are many models of development, from “pull only” (where maintainers decide what to take, and is used when developing Linux) to “shared push” (which acts like a centralized system). A distributed VCS gives you flexibility in how a project is maintained.

Practice And Scathing Ridicule Makes Perfect

I’m a DVCS newbie, but am happy with what I’ve learned so far. I enjoy SVN, but it’s “fun” seeing how easy a merge can be. My suggestion is to start with Subversion, get a grasp for team collaboration, then experiment with a distributed model. With the proper layout a DVCS can do anything a centralized system can, with the added benefit of easy merging.

Online Resources

- Mercurial has an excellent book. On Windows you may need diffing/merging software or TortoiseMerge (if you have TortoiseSVN installed).

- Darcs has a detailed wikibook (has some math theory about changes).

- Git was created by Linus Torvalds. Here’s an interesting lecture on DVCS; prepare to be berated for using a centralized system:

Notable Quotes:

- “How many have done a branch and merged it? How many of you enjoyed it?”

- “When you do a merge, you plan ahead for a week, then set aside a day to do it.”

- “Some people have 5, 10, 15 branches”. One branch is experimental. One branch is maintenance, etc.

- “CVS — you don’t commit. You make changes without committing. You never commit until it passes a giant test suite. People make 1-liner changes, knowing it can’t possibly break.”

So good luck, and watch out for the holy wars. Feel free to share any tips or suggestions below.